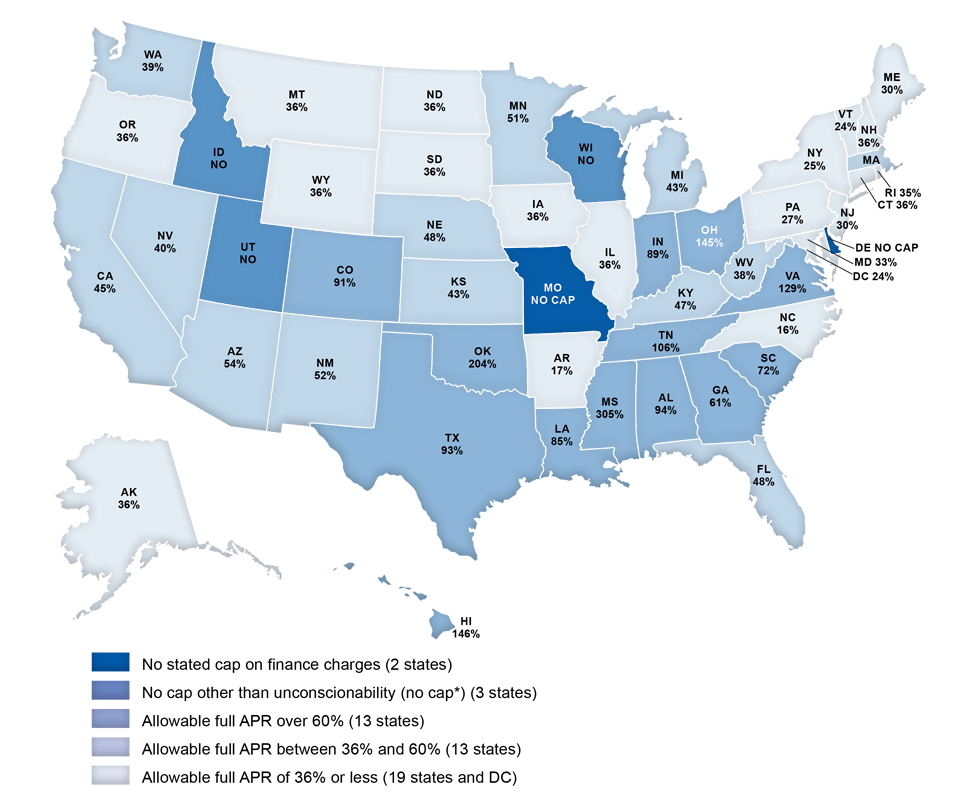

Caps on interest rates and loan fees are the primary vehicle by which states protect consumers from predatory lending. Forty-five states and the District of Columbia (DC) currently cap interest rates and loan fees for at least some consumer installment loans, depending on the size of the loan. However, the caps vary greatly from state to state, and a few states do not cap interest rates at all.

For a $500, six-month installment loan, 45 states and DC cap rates, at a median of 39.5%.

- 19 states and the District of Columbia cap the annual percentage rate (APR) at 36% or less.

- 13 states cap the APR between 36% and 60%.

- 13 states cap the APR at more than 60%.

- Three states—Idaho, Utah, and Wisconsin—require only that the loan not be “unconscionable” (a legal principle that bans terms that shock the conscience).

- Two states—Delaware and Missouri—impose no cap at all.

Map 1: APRs Allowed for Six-Month $500 Installment Loan

This map shows the maximum APRs allowed by the states for closed-end installment loans (loans in which the amount borrowed and the repayment period are set at the outset) by licensed non-bank lenders.

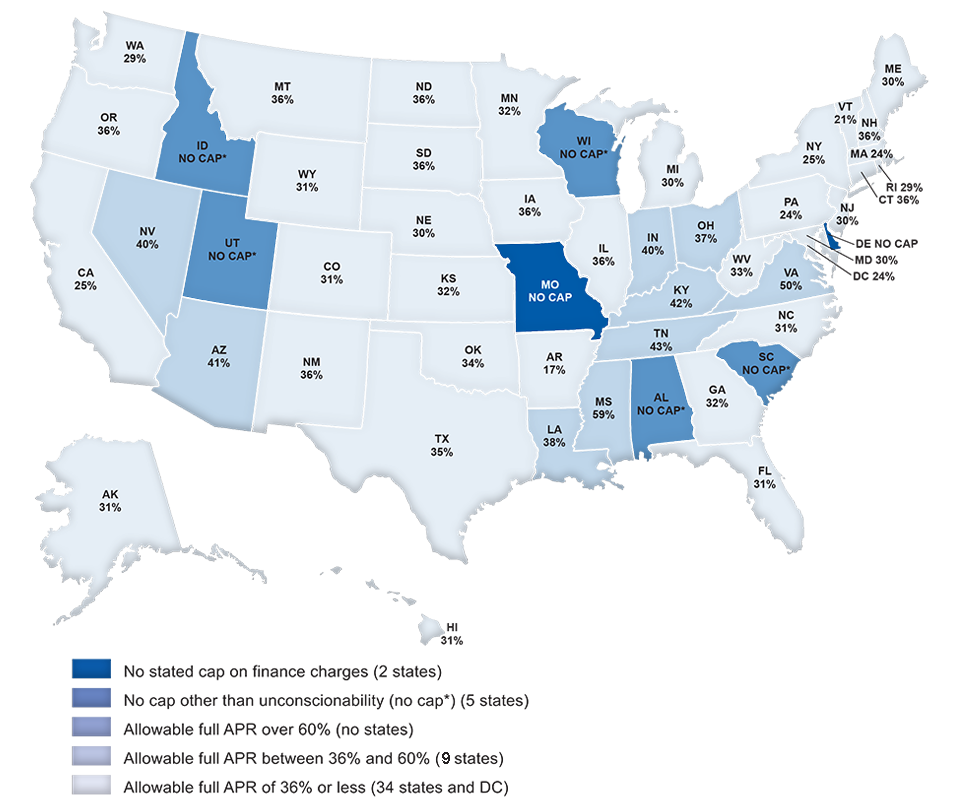

For a $2,000, two-year installment loan, 43 states and DC cap rates, at a median of 32% APR.

- 34 states and the District of Columbia cap the APR at 36% or less.

- 9 states cap it between 36% and 60% APR.

- Five states—Alabama, Idaho, South Carolina, Utah, and Wisconsin—require only that the loan not be “unconscionable.”

- Two states—Delaware and Missouri—impose no cap at all.

Map 2: APRs Allowed for Two-Year $2,000 Installment Loan

This map shows the maximum APRs allowed by the states for closed-end installment loans (loans in which the amount borrowed and the repayment period are set at the outset) by licensed non-bank lenders.

Why States Should Cap Interest Rates and Fees

Caps on interest rates and loan fees are the primary vehicle by which states protect consumers from predatory lending. In the absence of rate caps, exploitive lenders move into a state, overwhelming the responsible lenders and pushing abusive loan products that trap low-income consumers in never-ending debt.

| “[It] was like I asked for help to dig out of this hole and just created a deeper hole for me to inhabit.” NPR interview of Sarah Ahmed, who borrowed $2,300 at 98% to rent an apartment and get her young son set up in an after-school program. |

Interest rate caps are more than numbers: they are reflections of society’s collective judgment about moral and ethical behavior. Interest rate caps embody fundamental values.1 Interest rate caps also reflect an assessment about the upper limits of sustainable lending that does not undermine individual or societal economic stability. When states eliminate high-cost loans by imposing rate caps, consumers generally agree that they are better off and express relief that the loans are no longer available.2 Elimination of high-cost loans spurs an increase in affordable loans, benefiting all borrowers.3

In addition to limiting the cost of the loan for the borrower, limits on finance charges encourage lenders to ensure that the borrower has the ability to repay the loan. Excessive interest rates enable lenders to profit from loans even if many borrowers eventually default.4 Knowing that it will be made whole even if the borrower defaults, or that it can recoup defaults from exorbitant rates on others, the lender has little incentive to ensure that each borrower can actually afford to repay the loan in full on its terms.

High-cost loans, including high-cost installment loans, have a disproportionate impact on communities of color.5 Payday lenders have long targeted these communities.6 High-cost loans do not promote financial inclusion, but drive borrowers out of the banking system and exacerbate existing disparities.7

The APR is an Essential Standard for Measuring and Comparing the Cost of a Loan

The rates listed above are the annual percentage rates (APRs) as calculated under the Truth in Lending Act (TILA) for installment loans and include both period interest and fees. The APR is a critical way to measure and compare the cost of a loan, because it takes both interest and fees, and the length of the repayment period into account. It provides a common, apples-to-apples comparison of the cost of two different loans, even if they have different rate and fee structures or are used to borrow different amounts for different periods of time.

The Military Lending Act (MLA), which places a 36% APR cap on loans to members of the military and their families, requires the APR to take into account not just interest and fees but also credit insurance charges and other add-on charges. The MLA is also far more accurate than TILA as a disclosure of the cost of open-end credit such as credit cards. Because of this, the MLA APR is the gold standard, both for purposes of cost comparison and for purposes of legal rate limits. However, because of the difficulty of identifying the cost of credit insurance and other add-ons allowed, in the abstract, by the various state laws (as opposed to calculating the MLA APR for a given loan), we have used the TILA APR rather than the MLA APR in the rates displayed above.

For detail about how we calculated the APRs, see the Appendix.

Significant Changes in the States Since Mid-2021

Seven states made significant changes affecting their APR caps since we issued our last report in mid-2021. North Dakota and New Mexico made the most significant improvements. In North Dakota, the state legislature imposed a 36% APR cap on all non-bank loans in the state. Previously, there was no cap at all that applied to loans over $1,000. New Mexico reduced its APR cap from a predatory-level 175% to 36%, plus a fee of 5% of the loan amount for loans of $500 or less. Also on the plus side, Maine tightened its anti-evasion provision.

On the other hand, the Oklahoma legislature amended its lending laws to allow another junk fee, just three years after it increased the allowable per-month fees for small loans, thus continuing its practice of chipping away at consumer protections. Mississippi extended the sunset date of its highly abusive “Credit Availability Act” for four more years, and Wyoming repealed special protections that had formerly applied to loans at the high end of the rates it allows. Finally, Hawaii repealed its payday loan law, but replaced it with a new law that greatly increases the allowable APRs for installment loans of up to $1,500.

Louisiana consumers narrowly escaped the effects of a bill that would have allowed an APR of almost 300% on a $500 6-month loan. Governor John Bel Edwards’ veto of S.B. 381 on May 31 protected Louisiana families from this highly abusive proposal.

Details about the new laws:

Hawaii repealed its payday loan law, but in its stead enacted a new law, H.B. 1192, which allows longer and larger high-rate loans. For a 6-month loan of $500, the new law increases the allowable interest rate from 25% to a jaw-dropping 146%.

Maine added a strong anti-evasion provision to its non-bank lending law, which places a 30% APR cap on all installment loans under $2000, with a lower cap on larger loans. The new law, L.D. 522 (S.P. 205), is targeted in particular at rent-a-bank lenders that purport to launder their loans through banks as a way of evading state lending laws.

Mississippi enacted H.B. 1075, which extends the sunset date of its “Credit Availability Act” from July 1, 2022 to July 1, 2026. This Act allows highly abusive installment lending, with interest rates of 300% on four- to twelve-month loans of up to $2,500.

New Mexico greatly improved its protection of consumers from predatory lending by enacting H.B. 132, effective January 1, 2023. The new law caps interest on installment loans at 36% (plus a fee of 5% of the loan amount for loans of $500 or less, resulting in a 52% APR for that sample loan). The state had formerly allowed an APR of 175% for installment loans.

North Dakota put an end to high-cost installment lending in the state by enacting S.B. 2013, effective August 1, 2021. The bill imposes a 36% APR cap on all non-bank loans in the state. Previously, the state had no cap at all on the interest and fees that could be charged for non-bank loans over $1,000.

Oklahoma enacted S.B. 796, which raises allowable interest rates for certain installment loans, and allows non-bank lenders to add a junk fee of $38.85 to every loan. As a result, the APR that can be charged for a $2,000 two-year loan increases from 27% to 34%.

Wyoming formerly divided non-bank loans to consumers into two categories: “supervised loans,” which were subject to more restrictions on their terms but could charge 36% on the first $1000 and 21% on the remainder, and all other loans, for which the interest rate was capped at 10%. Effective July 1, 2021, H.B. 8 eliminates this distinction and allows the higher rates to be charged on all loans covered by the state Consumer Credit Code. The bill also repealed all the special protections that had applied to supervised loans.

Earlier Changes in State Lending Laws: 2017 to Mid-2021

Major changes in the states from 2017 to mid-2021 are summarized in the table below and described in more detail in NCLC’s May 2021 and February 2020 reports on state APR caps.

Table: Significant State Changes from 2017 to Mid-2021

Recommendations: A 36% APR Cap

To protect consumers from high-cost lending, states should:

- Cap APRs at 36% for smaller loans, such as those of $1,000 or less, with lower rates for larger loans.

- Prohibit loan fees or strictly limit them to prevent fees from being used to undermine the interest rate cap and acting as an incentive for loan flipping.

- Prevent loopholes for open-end credit. Rate caps on installment loans will be ineffective if lenders can evade them through open-end lines of credit with low interest rates but high fees.

- Ban the sale of credit insurance and other add-on products, which primarily benefit the lender and increase the cost of credit.

- Examine consumer lending bills carefully. Predatory lenders often propose bills that obscure the true interest rate, for example, by presenting it as 24% per year plus 7/10ths of a percent per day instead of 279%. Or the bill may list the per-month rate rather than the annual rate. Get a calculation of the full APR, including all interest, all fees, and all other charges, and reject the bill if it is over 36%.

The 36% rate cap is a widely accepted measure of the top acceptable rate and has been broadly supported by both lenders and the general public.8 But for loans in the thousands of dollars, 36% is too high, and a tiered structure that lowers rates as loans get bigger is appropriate. For example, for loans up to $10,000, Alaska allows 36% on the balance up to $850, and 24% on the remainder, with no additional fees.9

In addition, states should make sure that their loan laws address other potential abuses. States should:

- Require lenders to evaluate the borrower’s ability to repay any credit that is extended.

- Prohibit mechanisms, such as security interests in household goods and post-dated checks, that coerce repayment of unaffordable loans.

- Require proportionate rebates of all up-front loan charges when loans are refinanced or paid off early.

- Limit balloon payments, interest-only payments, and excessively long loan terms. An outer limit of 24 months for a loan of $1,000 or less and twelve months for a loan of $500 or less might be appropriate, with shorter terms for high-rate loans.

- Employ robust licensing and reporting requirements, including default and late payment rates, for lenders.

- Include strong enforcement mechanisms, including making unlicensed or unlawful loans void and uncollectible and providing a private right of action with attorneys’ fees.

- Tighten up other lending laws, including credit services organization laws, to prevent evasions.

See NCLC’s 2015 report on high-cost small loans for more details on each of these recommendations.

In the absence of rate limits at the federal level, state interest and fee caps are the primary bulwark against predatory lending. By following these guidelines, states can ensure that their laws are effective at protecting consumers.

Authors and Acknowledgments

Co-authors: Carolyn Carter, deputy director, National Consumer Law Center; Lauren Saunders, associate director, National Consumer Law Center; Margot Saunders, senior counsel, National Consumer Law Center. The authors thank NCLC colleagues Anna Kowanko, Andrew Pizor, Michelle Deakin, Stephen Rouzer, and Moussou N’Diaye for assistance, and Julie Gallagher for graphic design.

Related Resources

- Press Release

- Brief: After Payday Loans: Consumers Find Better Ways to Cope with Financial Challenges, August 2021

- Brief: Why Cap Interest Rates at 36%?, August 2021

- State Rate Caps for $500 and $2,000 Loans, June 2022

- Report: Predatory Installment Lending in the States: 2021, May 2021

- Report: Predatory Installment Lending in the States: 2020, February 2020

- Report: A Larger and Longer Debt Trap?: Analysis of States’ APR Caps for a $10,000 Five-Year Installment Loan, October 2018

- Report: Predatory Installment Lending in 2017: States Battle to Restrain High-Cost Loans, Aug. 2017

- Report: Misaligned Incentives: Why High-Rate Installment Lenders Want Borrowers Who Will Default, July 2016

- Report: Installment Loans: Will States Protect Borrowers from a New Wave of Predatory Lending?, July 2015

Publications

- Consumer Credit Regulation (see chapters. 9 & 10).

- Surviving Debt

Appendix

Methodology

This report addresses the APRs allowed by the non-bank lending laws of the fifty states and the District of Columbia for consumer installment loans of at least $500 for at least six months. It compares the maximum APRs that the states permit for two sample loans: a $500 six-month loan and a $2,000 two-year loan.

The purpose of an APR is to express the full cost of a loan on an annual basis, so that the costs of loans of different amounts, different lengths, and different mixtures of interest and fees can be compared to each other.10 The APR is especially important for revealing the full cost of a loan that charges fees in addition to a periodic interest rate. For example, Arizona allows 36% interest on a $500 six-month loan, but also allows an origination fee of 5% of the principal. Taking both the interest and this origination fee into account, the APR is 54%. If only the interest were allowed, the APR would be 36%.

A number of states have more than one statute under which our two sample loans can be made. If a state has several statutes, or its statute allows several different rates, we have used the highest rate allowed.

In many states, the allowed rates produce a higher APR for the $500 loan than for the $2000 loan. This occurs for two reasons. First, some states impose lower rate caps on larger loans. Second, in states where lenders are permitted to charge a fixed fee on top of the interest rate, that fee will have a greater impact on a smaller loan than a larger one. For example, an additional $50 charged on a $500 loan will have more of an impact on the APR than the same $50 fee will have on a $2,000 loan.

Many state lending laws have ambiguities that affect the calculation of the APR. For example, a lending law may allow a lender to charge an origination fee without specifying whether it can also charge interest on that fee. In the absence of clear statutory language or regulatory guidance, in our calculations we treated origination fees as amounts that can be added to the principal and on which interest can be charged. For other ambiguities, we have used our best judgment to find an interpretation that seems consistent with the statutory language and the intent of the statute, subject to correction if we are able to get clarification from regulators. Policymakers should consider issuing regulations or other guidance to close loopholes created by these ambiguities that high-cost lenders could exploit.

A thorough discussion of credit math calculations under state lending laws may be found in National Consumer Law Center, Consumer Credit Regulation Ch. 5 (3d ed. 2020).

Endnotes

1 See National Consumer Law Center, Consumer Credit Regulation § 1.3.2 (3d ed. 2020) (“CONSUMER CREDIT REGULATION”) (tracing the origin of the general usury laws on the books in many states today to England’s laws before American independence).

2 National Consumer Law Center, After Payday Loans: Consumers Find Better Ways to Cope with Financial Challenges (Aug. 2021).

3 Id.

4 National Consumer Law Center, Misaligned Incentives: Why High-Rate Installment Lenders Want Borrowers Who Will Default (July 2016).

5 S. Ilan Guedj, Ph.D., Report Reviewing Research on Payday, Vehicle Title, and High-Cost Installment Loans 9 (May 14, 2019).

6 See, e.g., Brandon Coleman & Delvin Davis, Center for Responsible Lending, Perfect Storm: Payday Lenders Harm Florida Consumers Despite State Law at 7, Chart 2 (March 2016).

7 CFPB, Online Payday Loan Payments at 3-4, 22 (April 2016).

8 See See Lauren Saunders, National Consumer Law Center, Why Cap Interest Rates at 36%?, August 2021

9 Alaska Stat. § 06.20.230.

10 See 15 U.S.C. § 1601(a) (“It is the purpose of [the Truth in Lending Act, which requires disclosure of the APR] to assure a meaningful disclosure of credit terms so that the consumer will be able to compare more readily the various credit terms available to him”); National Consumer Law Center, Truth in Lending § 1.1.1 (10th ed. 2019) (purpose of TILA to provide uniformity and enable comparison of disclosures of cost of credit).